Generating Memoji from Photos

Updated 10/31/2018: Added the link to the source.

Are you satisfied with your Memoji? :) Did you feel a bit lost when trying to choose the right chin or eyes? Wouldn’t it be cool if an algorithm could generate a Memoji from a photo?

In this post I’ll talk about my very basic attempt at using a neural network to generate Apple Memoji characters from real world photos of people. Specifically, I tested VGG16 Face, a network trained for face recognition to see how well it would perform when comparing real world photos with Memoji that “look like” various subjects. I then used it to guide the selection of features and create Memoji for new subjects.

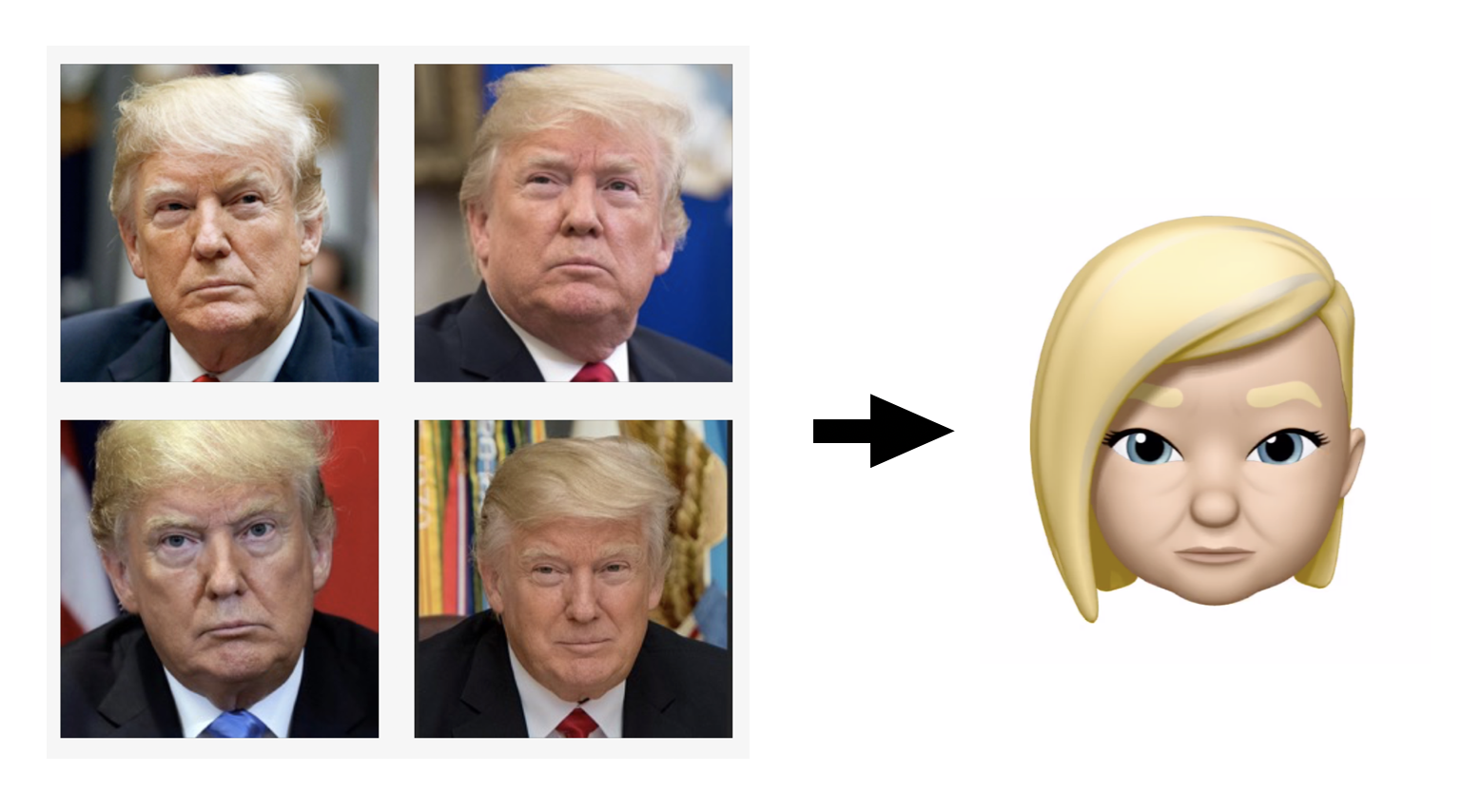

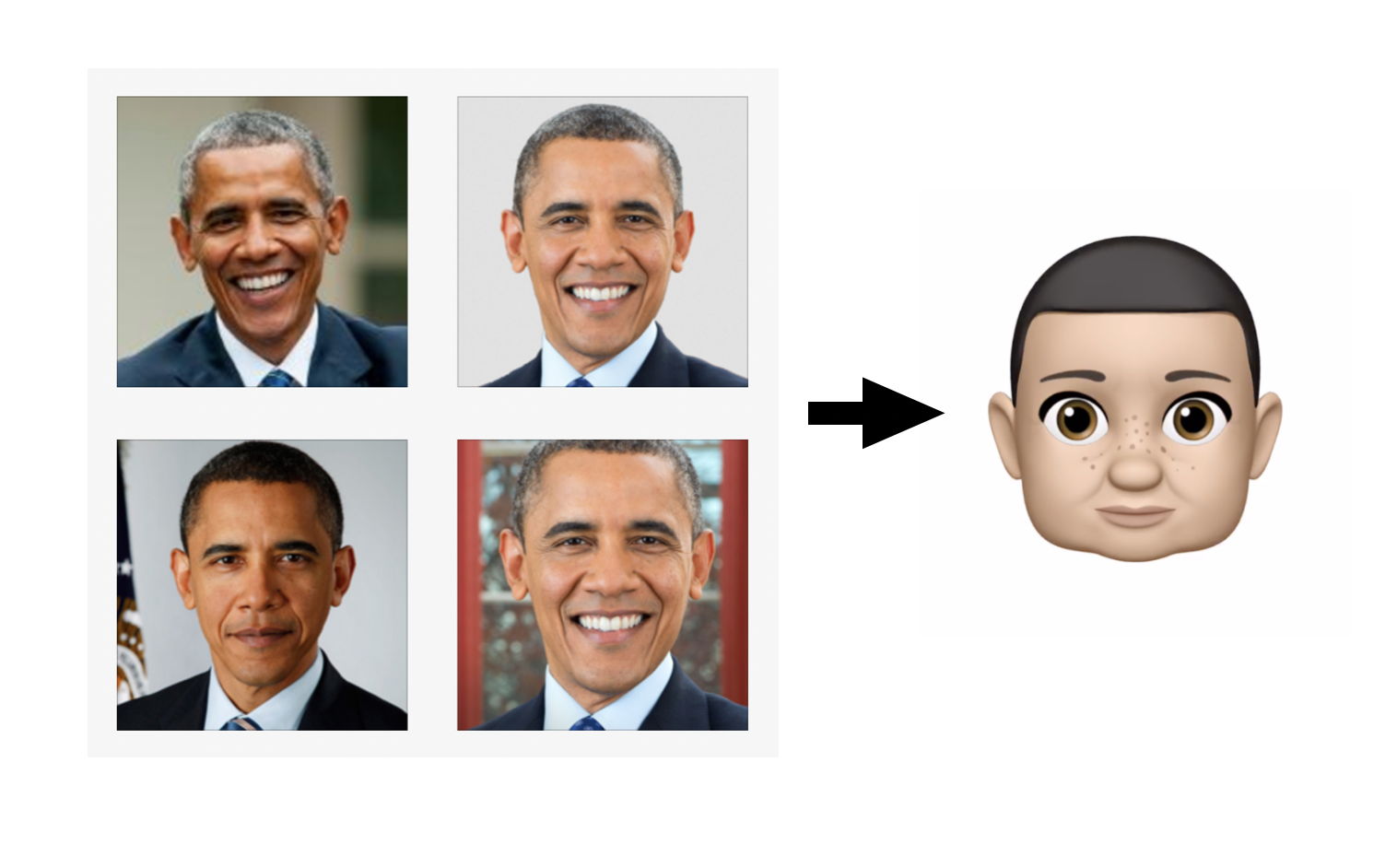

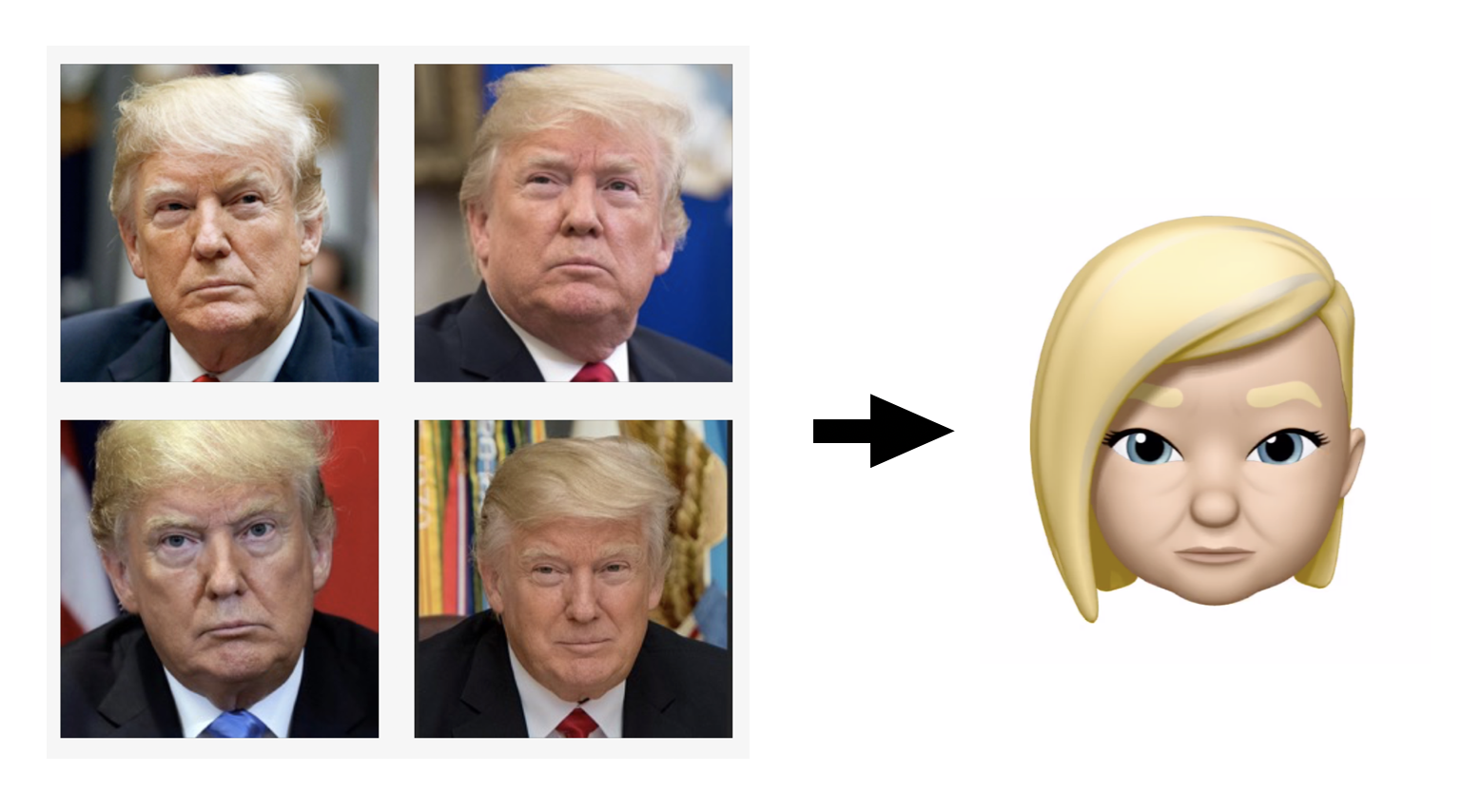

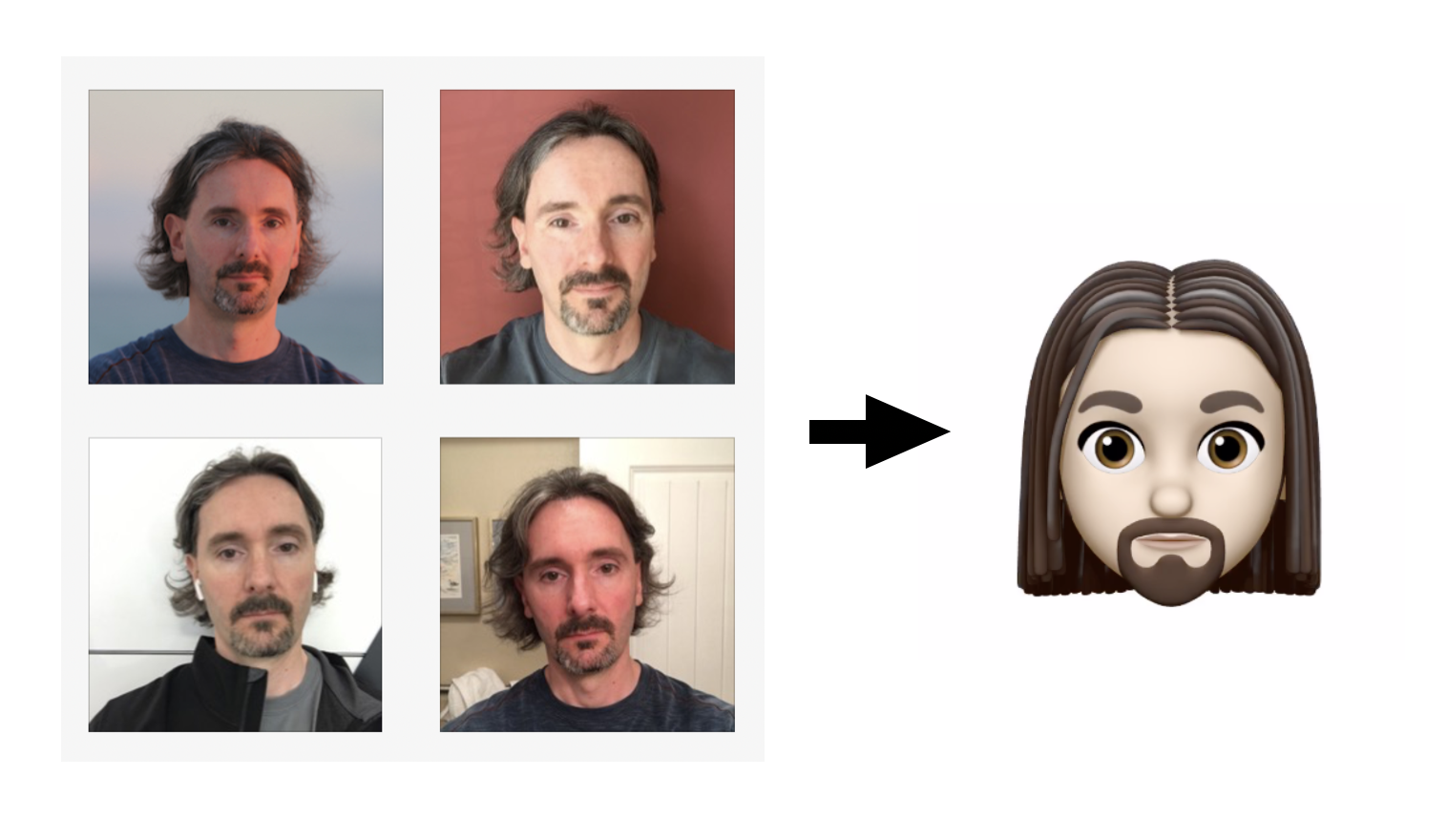

Memoji generated from photos with guidance from a neural network.

Spoilers

The images above show a couple of the results. While they leave a lot to be desired, I think there are some interesting choices buried in there and I was excited to find that the simple approach taken here actually worked at all. I half expected that the network would not “see” these Memoji as faces. There are also a bunch of factors working against us here and let me state a few up front:

Caricatures

First, there is the question of what someone “looks like” in a cartoonish form. Caricatures exaggerate a person’s most distinctive features. But some features like hair style are not really intrinsic to the person and vary a lot from photo to photo and day to day. For this reason it seems likely that a neural network trained to recognize individuals would capture information about hair style in an abstract way that allows for this variation. Conversely this means that it may not be ideal for generating hairstyles from arbitrary choices.

Skin Tone and Hair Color

Inferring skin tone from photos taken in random lighting conditions is a hard and my simple test setup reflected this by doing a very poor job at it. In my tests the network generally picked lighter skin choices and didn’t always differentiate well between realistic and unrealistic options (not shown). Also, while the test rig did a pretty good job at differentiating dark and lighter hair it more or less failed when presented with brightly colored hair and I’ll have some thoughts on this toward the end.

This article on normalizing facial features and skin tone looks pretty cool: Synthesizing Normalized Faces from Facial Identity Features

No API

Experimenting with Memoji is limited by the fact that there is currently no API for creating them procedurally. (No straightforward way to automate their creation in iOS). This limits how effectively we can search the space of possible Memoji as part of any generation process. Ideally we’d want to use a genetic algorithm to to exhaustively refine combinations of features rather than rely on their separability, but this was not possible in the simple experiment here.

Photo Selection

The choice of which photos to include as reference material has a large impact on the result. Some photos produced subjectively better results than others and in many cases it wasn’t clear to me why. In general I tried to find representative, tightly cropped, forward facing photos. As I’ll discuss below, for each feature choice I averaged scores based on at least four reference photos.

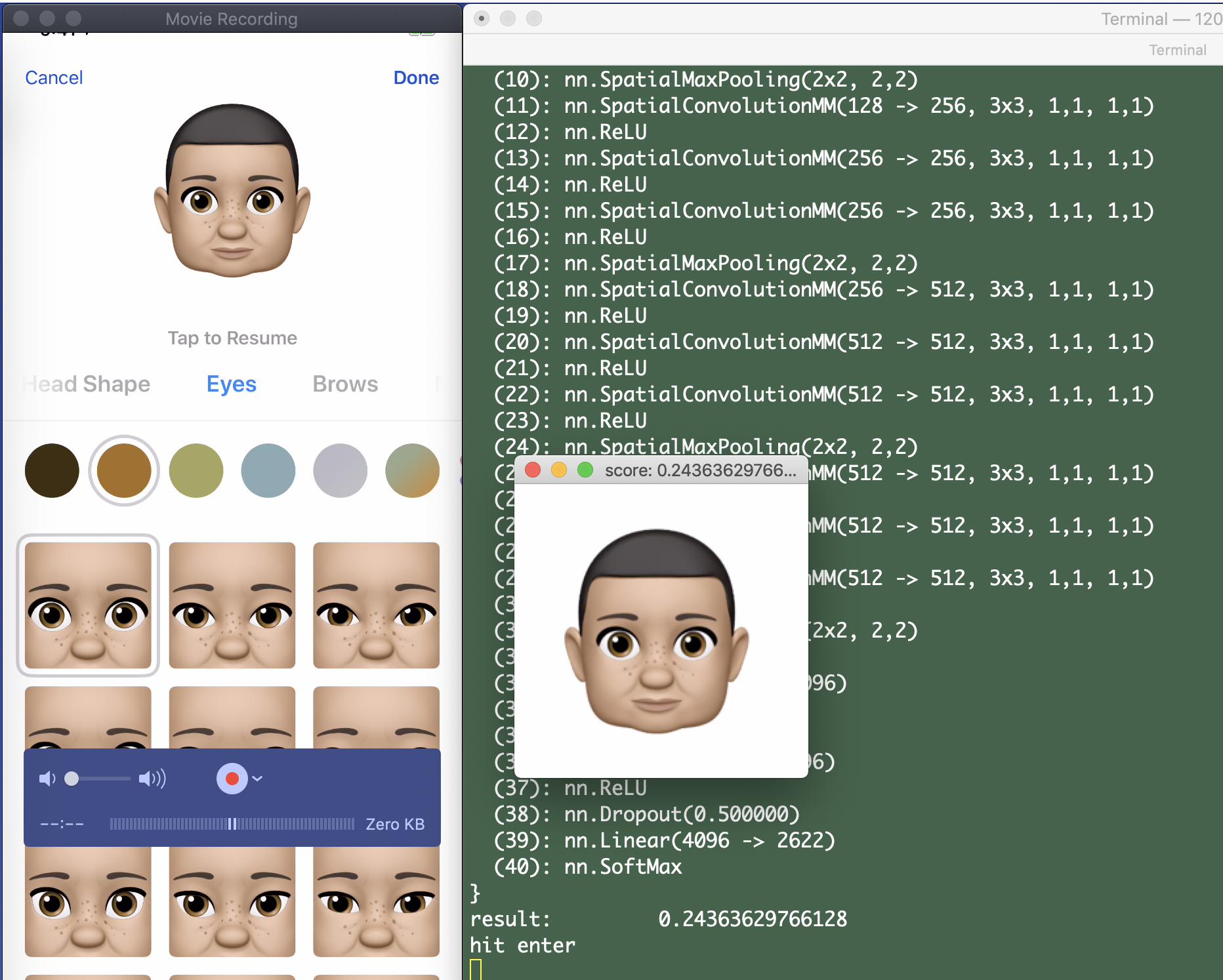

The Network and Setup

The actual code for these tests was pretty small. I’ll run through the setup and link to the source at the end.

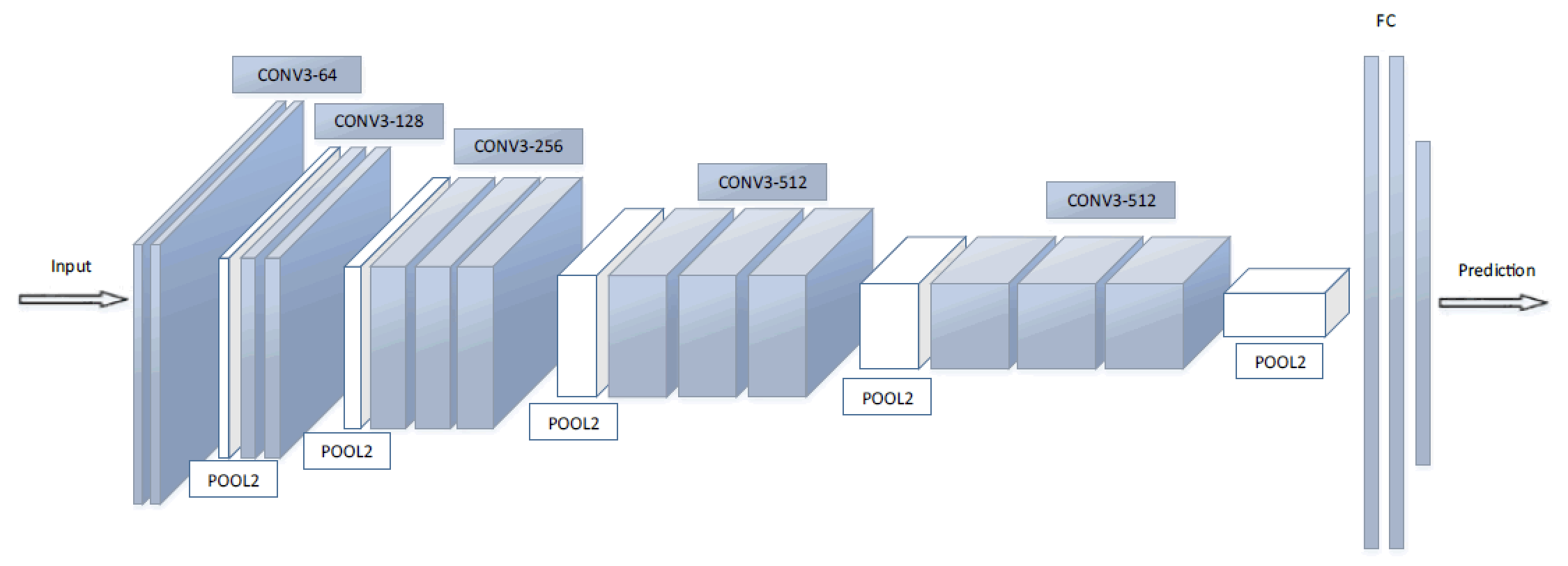

VGG

VGG is a popular convolutional neural network architecture used in image recognition. VGG Face is an implementation of that architecture that has been trained specifically to recognize faces. Its creators have made the fully trained network (the layer details and learned weights required to run the network) available to download and use. This is what makes goofy experiments like this possible, whereas training a network like this from scratch would require a prohibitive amount of finely curated data and a lot of compute time. The downloadable weights file representing the final trained network is half a gigabyte!

Torch

For these tests I used the Torch scientific computing framework. Torch provides the environment needed to run the VGG model. It offers a scripting environment based on Lua, with libraries for performing math on Tensors (high dimensional arrays of numbers) and primitive building blocks for the layers of the neural network. I chose Torch simply because I’ve used it before.

Torch can load the provided VGG Face model for us and run an image through it with just a few lines of code. The basic flow is:

-- Load the network

net = torch.load('./torch_model/VGG_FACE.t7')

net:evaluate()

-- Apply an image

img = load_image(my_file)

output = net:forward(img)

There are a couple of steps involved in loading and normalizing the image, which you can find in the supplied source code.

Working with the Layers

As shown in the diagram above, VGG composes layers of different types. Starting with a Tensor holding the RGB image data, it applies a series of convolutions, poolings, weightings, and other types of transformations. The “shape” and dimensionality of the data is changed as each layer learns progressively more abstract features. Ultimately the network produces a one dimensional, 2622 element prediction vector from the final layer. This vector represents the probabilities of matching one of a set of specific people on which the network was trained.

In our case we do not care about those predictions but instead we want to use the network to compare our own sets of arbitrary faces. To do this we can utilize the output of a layer just below the prediction layer in the hierarchy. This layer provides a 4096 element vector that characterizes the features of the face.

output = net.modules[selectedLayer].output:clone()

While VGG16 is nominally a 16 layer sandwich, the actual implementation in Torch (and its neural network library nn) yields a 40 “module” setup. In this scheme layer 38 gives us what we want.

Similarity

What we’re going to do is essentially just run pairs of images through the network and compare the respective outputs using a simple similarity metric. One way to compare two very large vectors of numbers is with a dot product:

torch.dot(output1, output2)

This produces a scalar value that you can think of as representing how much the vectors are “aligned” in their high dimensional space.

For this test we want to compare a prospective Memoji with multiple reference images and combine the results. To do this I just normalized the value for each pair and averaged them to produce a “score”.

sum = 0

for i = 1, #refs do

local ref = refs[i]

local dotself = torch.dot(ref , ref)

sum = sum + torch.dot(ref, target) / dotself

end

...

return sum / #refs

The normalization means that the score for comparing an image to itself would yield 1.0. So for later reference higher “score” numbers mean greater similarity.

There are many other types of metrics we could use. Two other obvious possibilities are a euclidean distance or a mean squared error between the outputs. I briefly experimented with both of these but for reasons that I do not understand the dot product seemed to produce better results.

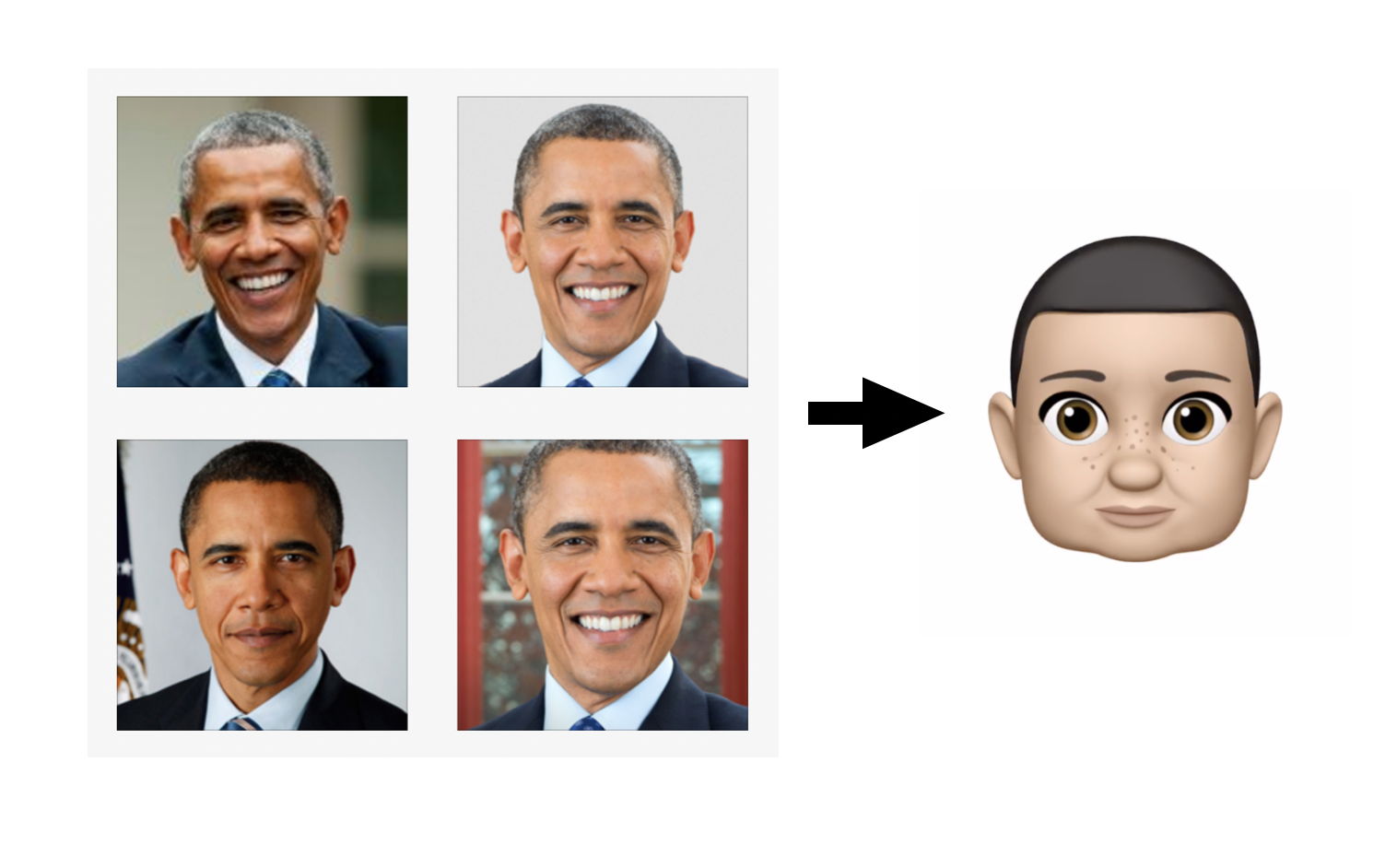

A First Test - The Lineup

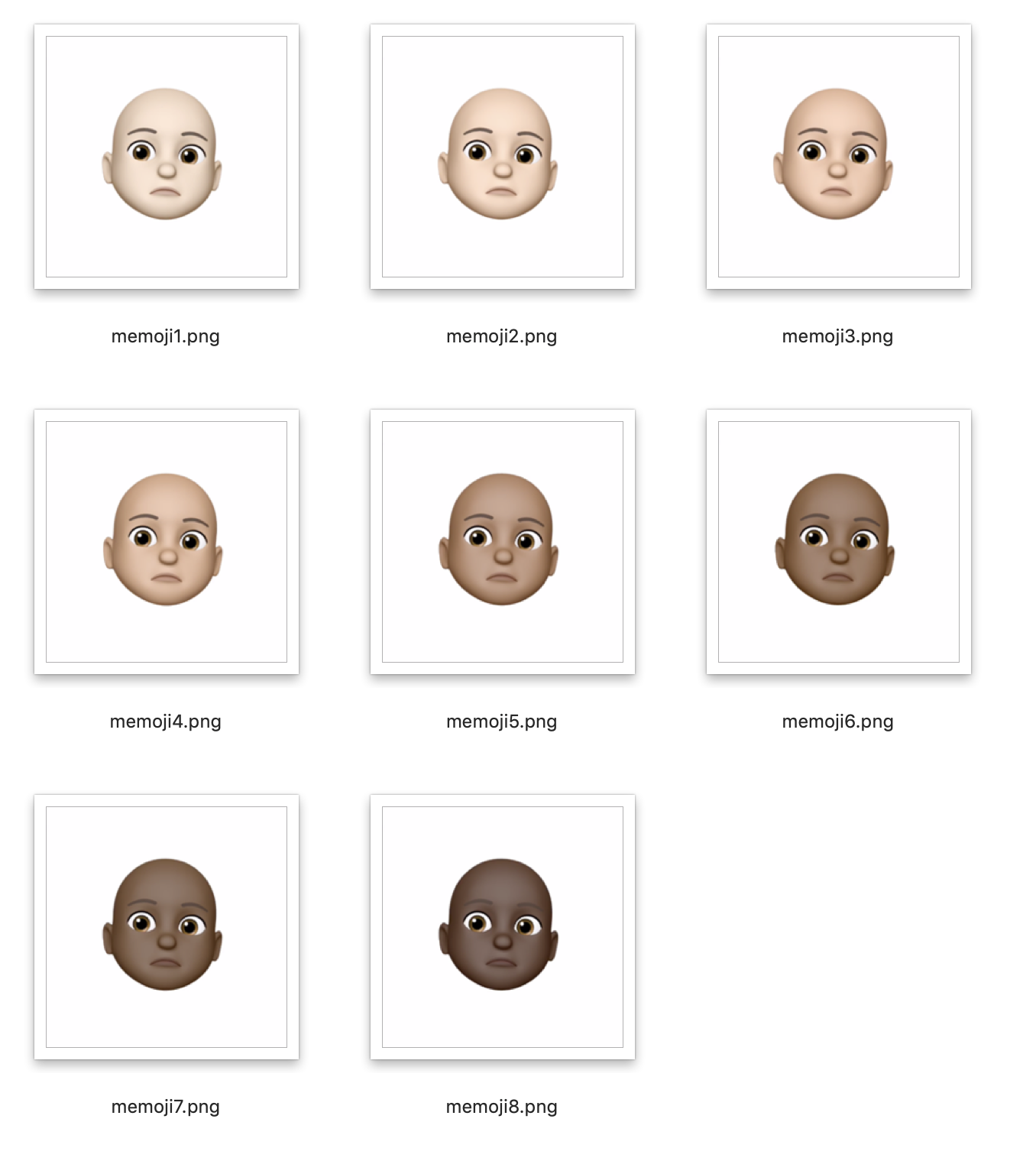

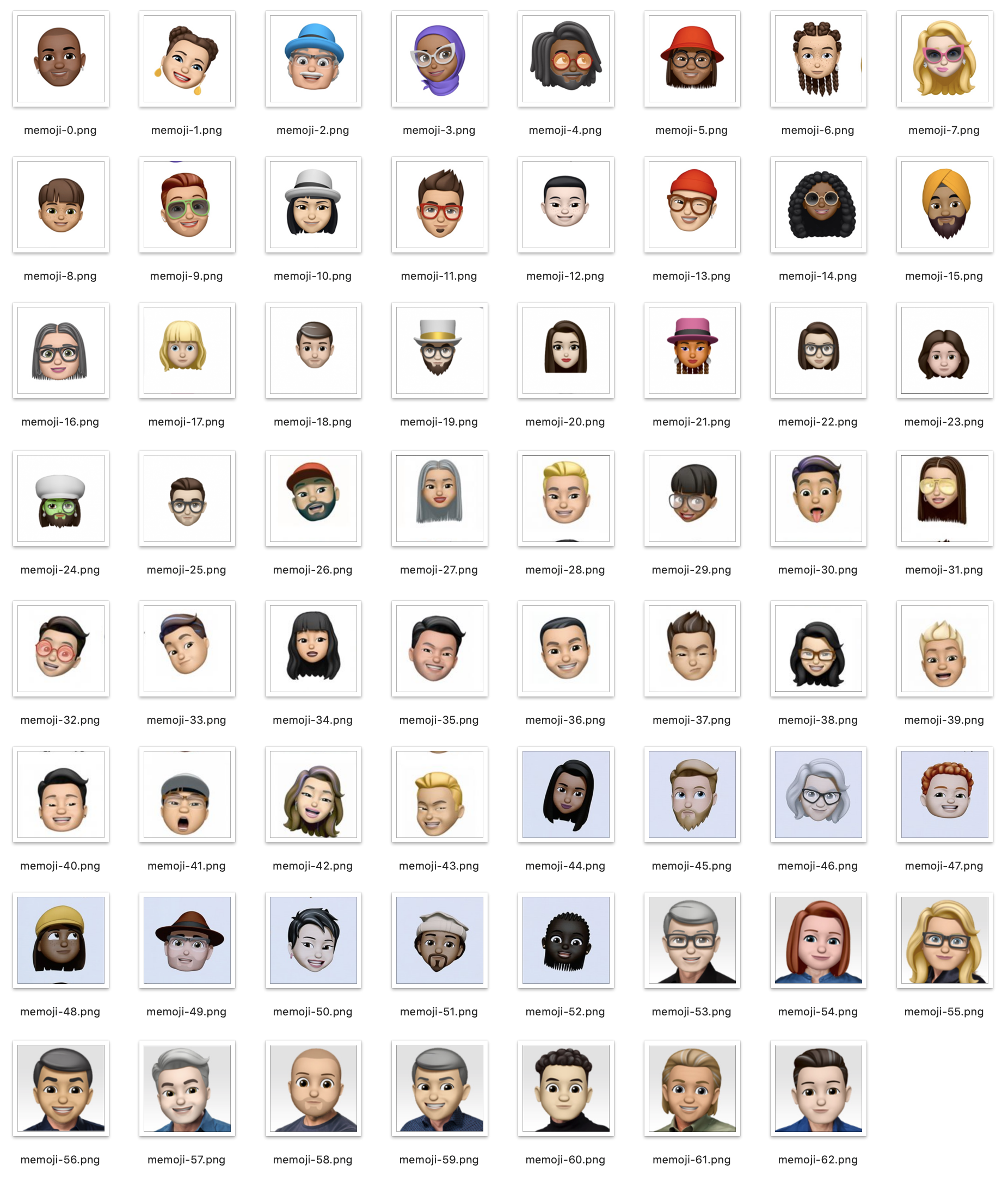

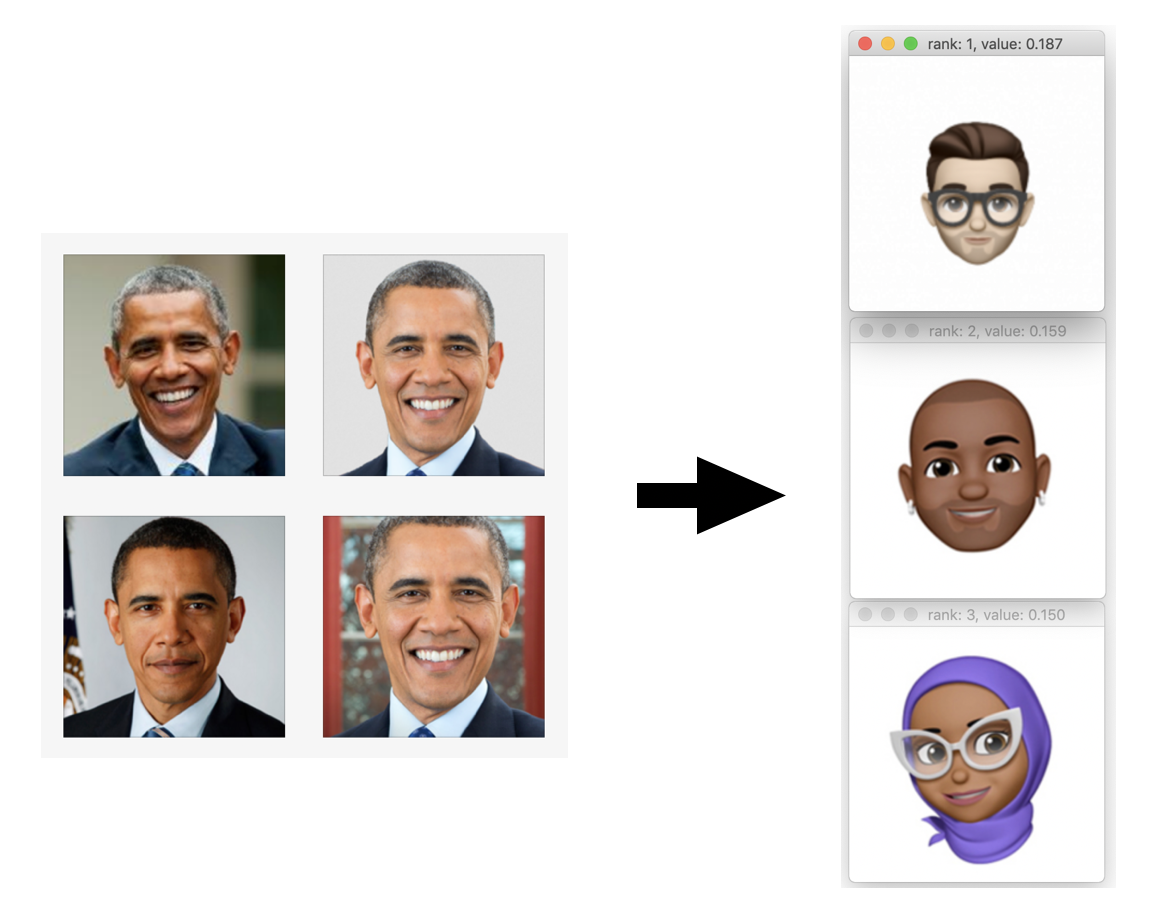

The first thing I wanted to validate was whether or not the face network would work with cartoonish Memoji faces at all. I started by grabbing a random collection of 63, human-looking Memoji from a google image search. (Most of these came from Apple’s demos).

I then chose one and asked the network to rank all of the Memoji and show me the top three picks based on this single reference.

The results are encouraging! Not only did it find the identical Memoji (ranked first with a score of 1.0) but the second and third choices were plausible too.

Real photos

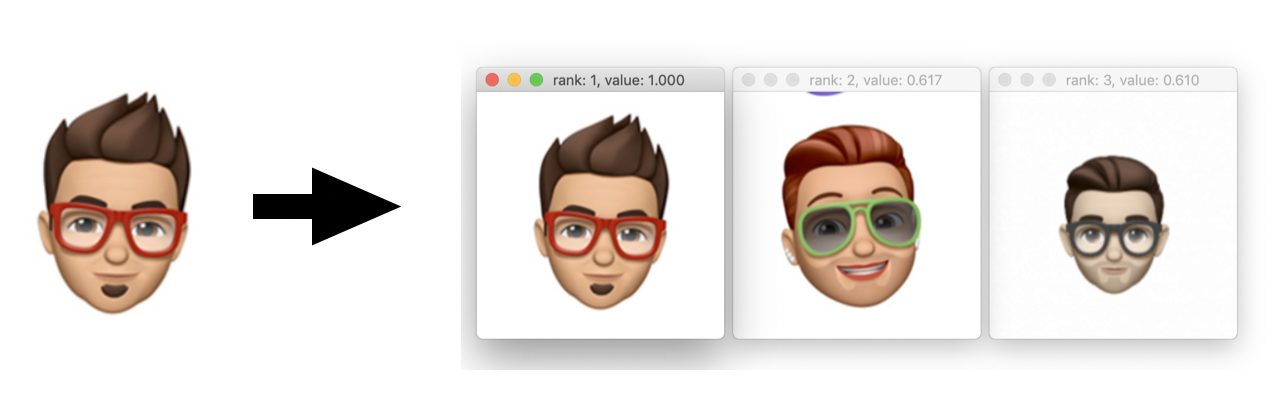

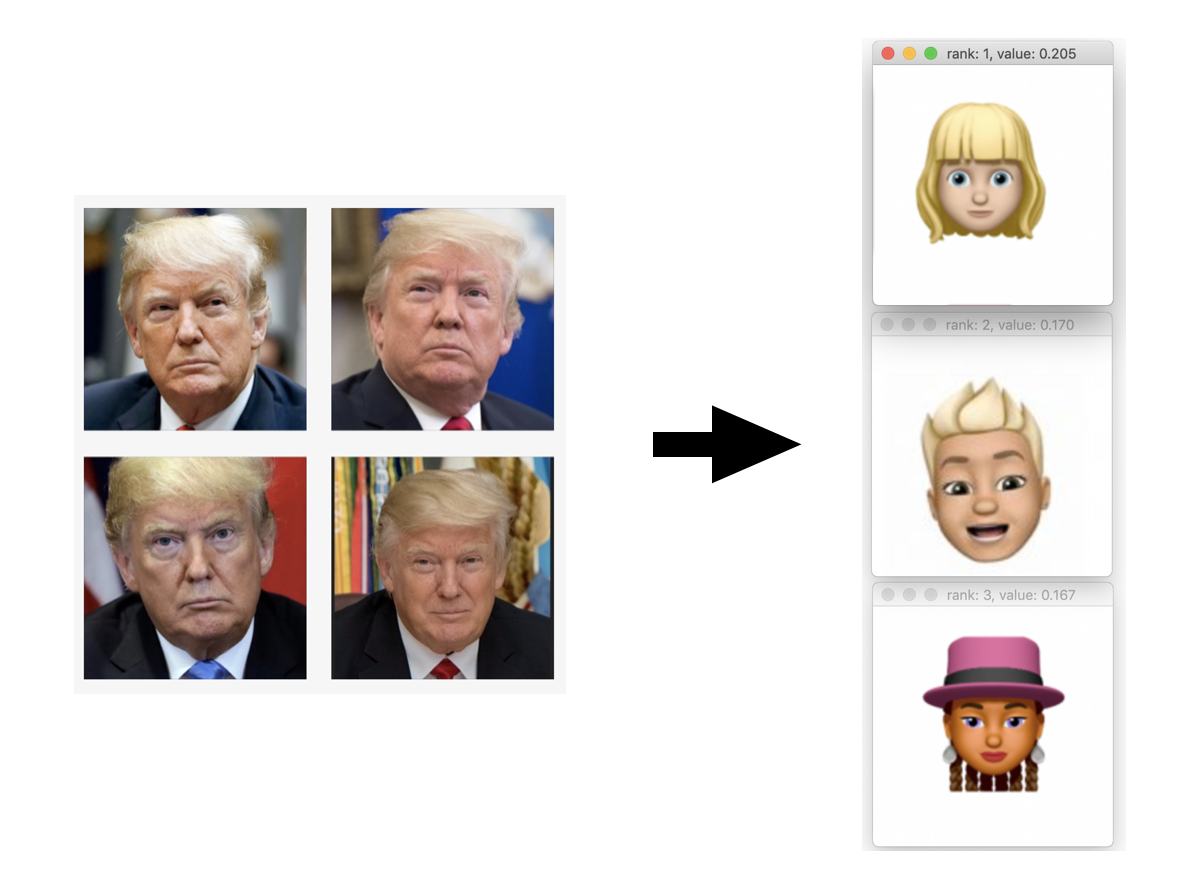

Now comes the “real” test: What would the network make of a real world photo when compared with these Memoji? I grabbed some photos of famous people and these were the results:

Ok, well, the results are interesting anyway, right? :) Keep in mind the limited set of Memoji that it had to choose among and that the dominant features the network is seeing in these images may not be what we expect. Also note how much lower the scores (the “confidences”) are in these comparisons than when comparing Memoji to other Memoji.

Let’s move on :)

The “Generation” Process

Next, I tried to turn this around and create a Memoji using the network to pick features. This is where it got sticky. As I mentioned, there’s no obvious way to automate the creation of a Memoji on iOS. While there would certainly be ways to do this with a jailbroken device or by hacking together captured artwork, I’m decided to keep this simple and just help the script push the buttons.

For the test rig I tethered my phone to my desktop with Quicktime Player’s Movie Recording feature and positioned it in a corner where the script could grab screenshots for processing. For each feature I ran through the possibilities, selecting each option and hitting enter on the keyboard to grab and rank the output.

This is obviously not ideal for several reasons: First, it’s a pain. (There are 93 hair choices by the way; Try running through those dozens of times.) More importantly, it only allows us to evaluate one feature difference at a time. In theory we could iterate on this and run through the tree of choices repeatedly until there were no changes suggested by the network, but even that isn’t perfect since it might only be a “local minimum” based on how we started. (If one feature affects the perception of another feature then the order of evaluation matters).

Did I mention that there are 93 hair choices? :)

My initial attempt at doing all of this was also frustrated by the fact that the head was tracking me and small movements would affect the scoring. After some wasted time I realized that I could simply cover the camera and the Memomji would stay in a fixed position :facepalm:.

Results

I spoiled some of the results at the beginning of this post, but they could use a little elaboration.

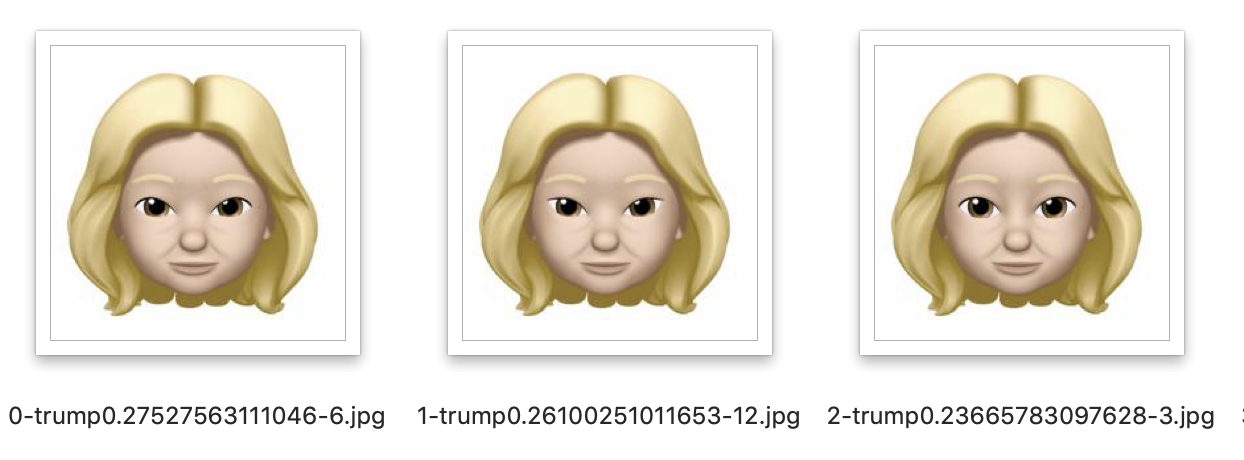

In a draft of this article I showed an image of President Trump in which I overrode the decision of the network about the choice of hair and picked one of the higher ranked ones myself (I did say “guided”) but I thought better of that and in all of the images shown here are the choices of the script.

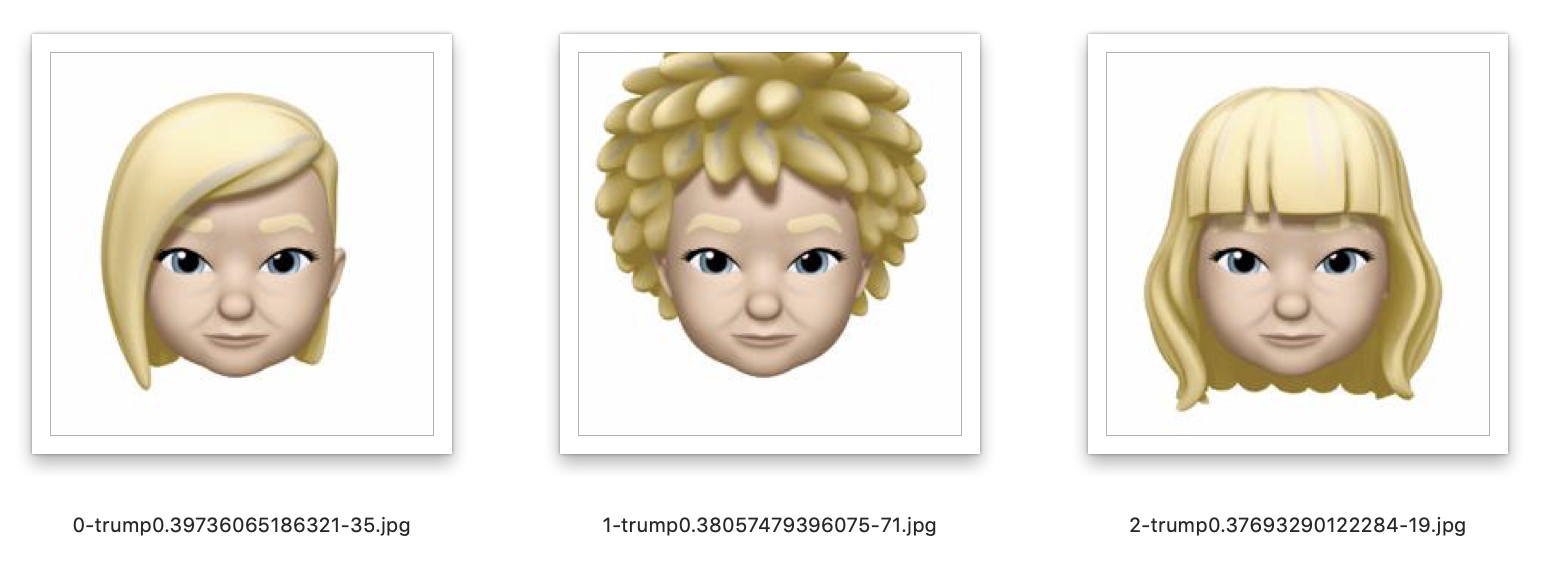

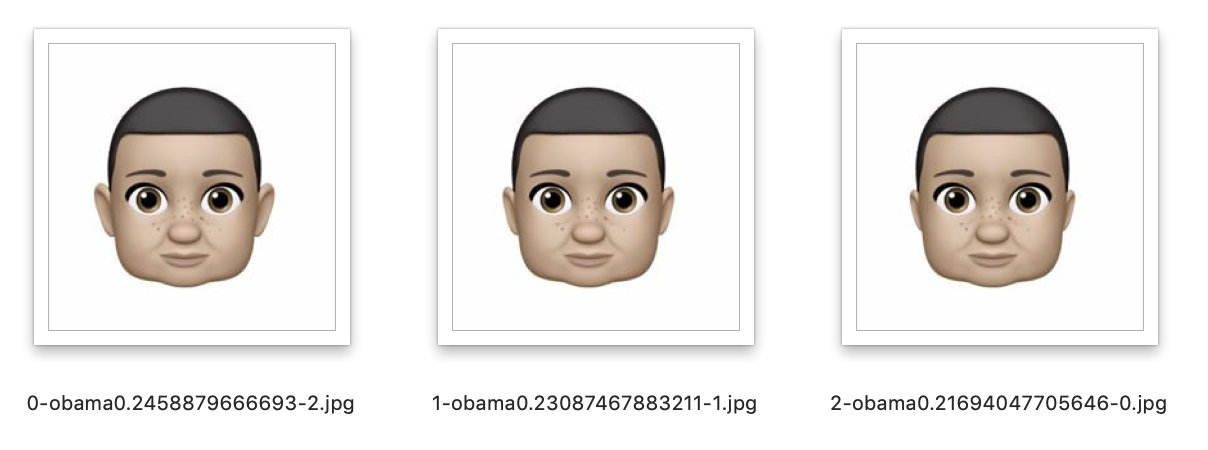

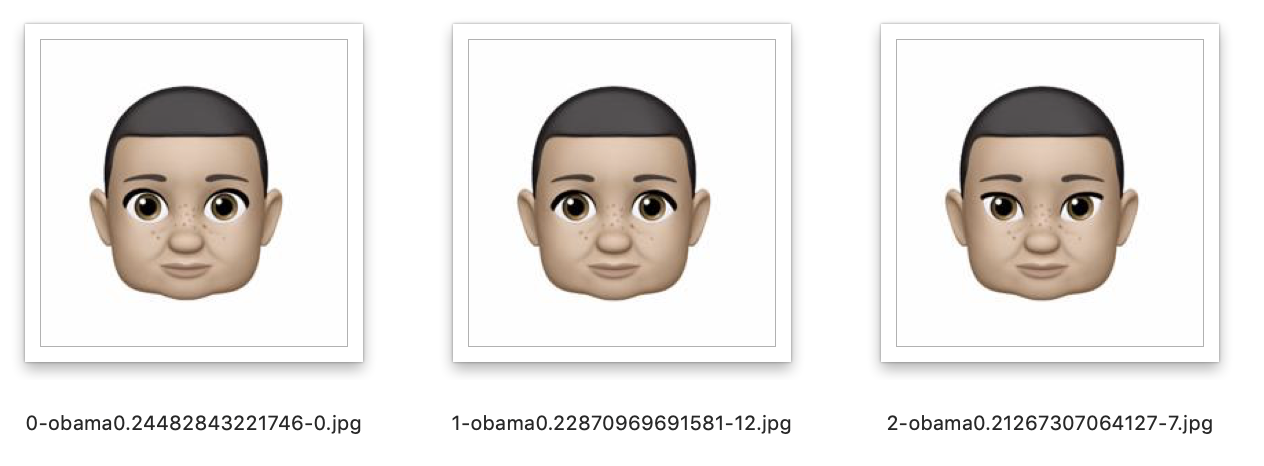

With that said, some feature choices seemed much more volatile than others: By this I mean that in some cases the top three choices made by the network were very similar but sometimes they were not. For example, these are the top three choices for President Trump’s hair:

Some characteristics did what I expected. For example, President Obama is said to have prominent ears and the network did rank the choices from largest to smallest.

Obama’s ear selection

But the choice of eyes varied quite a bit:

Obama’s eye selection

President Trump’s eye selection, on the other hand, was more consistent:

Trump’s eye selection

President Obama’s chin looks overly square to my eye, but after staring at it for a while now it kind of looks right to me. (This is the danger of letting too much subjectivity creep into this.)

Hair Color

I’ve already mentioned that skin tone was not differentiated very well at all. (Although in the Memoji selection test it did seem to make some correspondence?)

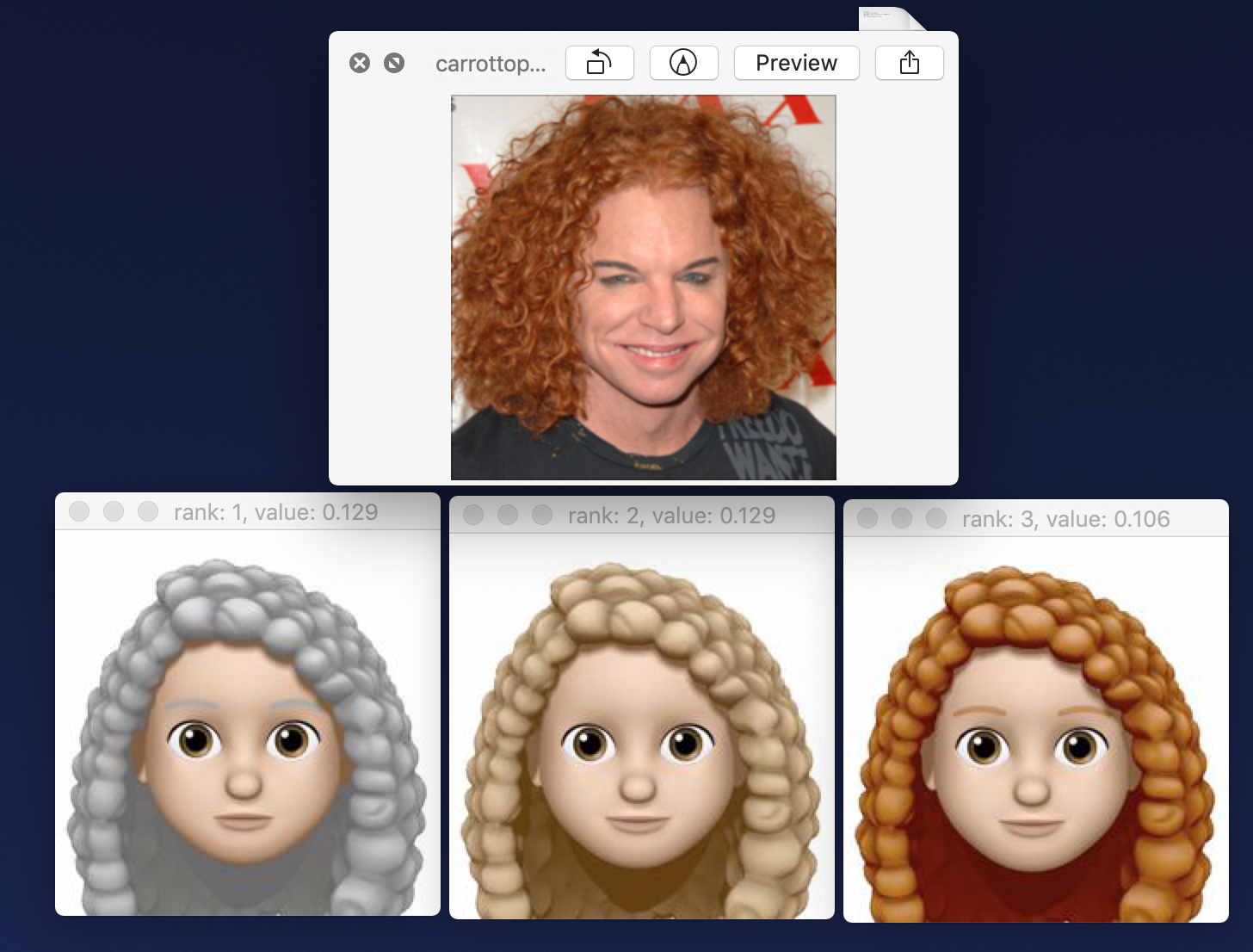

Hair color selection was also problematic. Hair color for President Trump and President Obama seemed fine but when I tried it on someone with bright read hair the network always wanted to pick gray:

Carrot Top hair color selection

Reddish hair was in the top three (of ten), but this was not a satisfying result. I tried many things to see if I could find factors that would affect this: I changed the way I pre-processed the image (thinking that perhaps I had the layers reversed or the normalization wrong). But I found that the choice of gray here was very stable even when I changed the input image drastically.

In another test I looked at the choices that other layers would make. Recall that we chose layer 38 since it is the highest layer that characterizes the face prior to the layer that makes a prediction about an individual person. However we can compare the choices lower layers, just to see how they would differ. In particular using our layer 32 instead of 38 often seemed to make a different and interesting choice where color was concerned. This layer corresponds to the last “pooling” layer in VGG16 right before the first “fully connected” layer and so perhaps it retains more spatial and color information. This layer and some lower layers did a better job at picking bright red for the color of Carrot Top’s hair. However they made subjectively worse choices for the rest of the images.

I also tried averaging hair color choices in various ways (by top three choices and by alternate network layers). The averaging actually sort of works for features too if you don’t mind a little blurring. These produced plausible results but ultimately nothing gave me bright red hair for Carrot Top :(

If anyone has any ideas here please write me!

The Source

You can get the Torch scripts that I used in this article at the github project: vgg-memoji. I will try to include the images that I used but if I receive complaints I may have to take them out. If they are gone when you get there and you still want to reproduce my results with the same data please contact me directly and I will send them to you.

The full VGG Face network can be downloaded from the Visual Geometry Group VGG Face web site.

All feedback, corrections, and suggestions are welcome.

UPDATE: Since writing this article I have switched decisively to PyTorch, a Python based environment with Torch integration. It’s stable / mature now and I find it much more pleasant to work in than Lua. (Go Intellij PyCharm!)

Me?

Pat Niemeyer is a Co-founder and software engineer at Present Company. He is the author of the Learning Java book series by O’Reilly & Associates and contributor to various open source projects.

For my Memoji above I allowed myself a few tweaks: The network chose black hair for me, which I changed to brown with gray highlights. It also chose gray eyes for some reason and a slightly different set of facial hair (though very close).